If you have ever read fiction, seen a movie or a play, then you know the characters are not real. The characters’ physical, behavioral and emotional likeness to people affects our understanding, specifically how we connect to their appearance and performance. The more relatable the players perform the created role, the more we trust the representation. It also tests our understanding of reality.

When we trust, our critical reasoning takes a breather.

AI apps, especially the Large Language Models’ “front” speaks to us in a manner that makes us engage easily. The comfort we derive from this guise also silences concern and quiets inner doubts. Not always, but the more representative of human interactions it appears the less wary we remain.

HyperWrite CEO Matt Shumer’s characterization as quoted in INC magazine caught my attention recentl.

“I like to describe AI as a brilliant intern, or even a child: It knows so much about things I don’t know, and it can be so helpful in so many ways. But sometimes it gets things wrong, or flat out lies. Not necessarily because it’s attempting to deceive; rather, because of limitations in its programming and the resources it’s pulling from.”

So what’s the problem?

Human perspective and perception unconsciously processes signals that cue internal reasoning. Plausibility of any represenation dampens those signals.

The more plausible the results the less consciously we question their origin, representation, or authority.

The nature of our internal representations of our environment, knowledge, skills and tools naturally extend to AI systems and give rise to our expectations from these systems. The comfort we gain from the representation also affects whether we engage or activate Our critical thinking.

Let’s test this.

Picture a robot. Hold that image.

Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner includes my namesake character Rachel. If you’ve seen the film you likely can picture her. Philip K Dick, who authored the original story in 1962 called her a replicant, not a robot. How does this representation match the image you are holding?

James Cameron’s epic film Avatar feature a population with blue shaded skin. Their actions, emotions and behavior are very relatable, and yet did you mistake them for humans?

Did you exercise any critical thinking in order to evaluate whether these fictional presentations were real? What truths if any do they share or expose for you?

The systems and tools that made it possible for these films to bring life to these characters is evolving rapidly. Whether represenation presents a problem or not is considerably older.

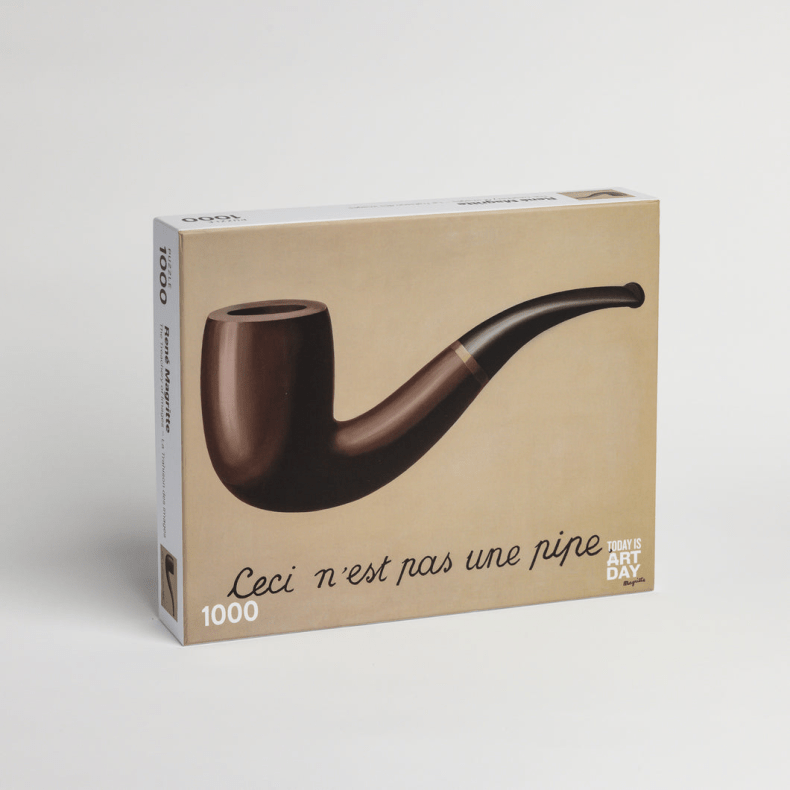

The surrealist painter Magritte provocations are often considered humorous, but that doesn’t diminish the gravity of the paradox.

The unsettling familiarity of any representation doesn’t deny the latter’s value, or usefulness. The evolution of tools and their accurate reproduction of tangible items isn’t the problem.

It’s more that the muscles that propel human learning is slower to evolve. I’m intrigued by what Shumer writes. “AI is going to keep changing, and fast. The models that exist today will be obsolete in a year … people who come out of this well won’t be the ones who mastered one tool. They’ll be the ones who got comfortable with the pace of change itself.”

The mor einfrastructure and artifacts that people create, the harder it becomes for people to make space cognitively and physically for something new. Your robot representation affects what you beleive and what you trust. As ever advancing technology outpaces the evolution of our representations, progress becomes difficult to evaluate and manage.

I’m looking for some models and methods and leaders.

What do you use?